How to Lose a Political Campaign

It’s been exactly one year since I was hired to work on the Joe Biden re-election campaign. Which then became the Kamala Harris campaign. Then the Harris-Walz campaign. But wait, stop. Let’s rewind.

It was the night of November 8, 2016, and I was in my last semester of college. This was the first political cycle I had followed with any real interest—I'd even attended a Bernie Sanders rally a few months earlier and was disappointed when he didn’t get the Democratic nod. Still though, I was excited. We were about to elect our first woman president. This was history in the making! I refreshed FiveThirtyEight until my fingers went numb and waited for the results to roll in.

Blue for New York popped up—which was predictable. Then a flash of red. Red state after red state started trickling in. But that was expected, everyone warned about a red mirage. Counting had hardly begun and some precincts had only reported 1% of votes tallied. Still, I had a sinking feeling in my stomach. I couldn’t bear to keep watching. I fell asleep around 10 p.m. LA time, telling myself that when I woke up, Hillary would be declared as the winner.

I woke up the next day and Donald Trump’s image smirked at me through my phone screen. I knew the next four years were going to be interesting for all the wrong reasons.

Three years passed and it was the summer of 2019. I was passively following the Democratic primaries which was a crowded field. Everyone claimed they could beat Trump. But one candidate caught my eye—Elizabeth Warren. She’d made waves when was silenced by Mitch McConnell during Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearing.

"Senator Warren was giving a lengthy speech. She had appeared to violate the rule. She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted."

It became a feminist rallying cry. Every woman could relate to being shut down mid-sentence by some dude. The phrase was everywhere—on mugs, bumper stickers, T-shirts. Since that moment, she had been on my radar. She reminded me of a strict but kind elementary school teacher—progressive but pragmatic, firm but fair.

I reached out to a Warren staffer and offered to volunteer my animation skills. They directed me to the general sign-up form. I filled it out, fully expecting nothing to happen.

Then as fate would have it—a few weeks later, I saw a job listing for the Warren campaign. They were hiring a full-time Motion Graphics Designer at their campaign headquarters in Boston. I applied immediately, interviewed with their Creative Director—and then... radio silence.

I was ghosted.

It had been too good to be true.

They probably hired someone with more political experience. I’d only worked in entertainment in LA. Never on a campaign.

But then—

Two months later, they reached out.

I got the job.

I packed up my entire life in LA and moved to Boston—wide-eyed, eager and ready to do work that mattered.

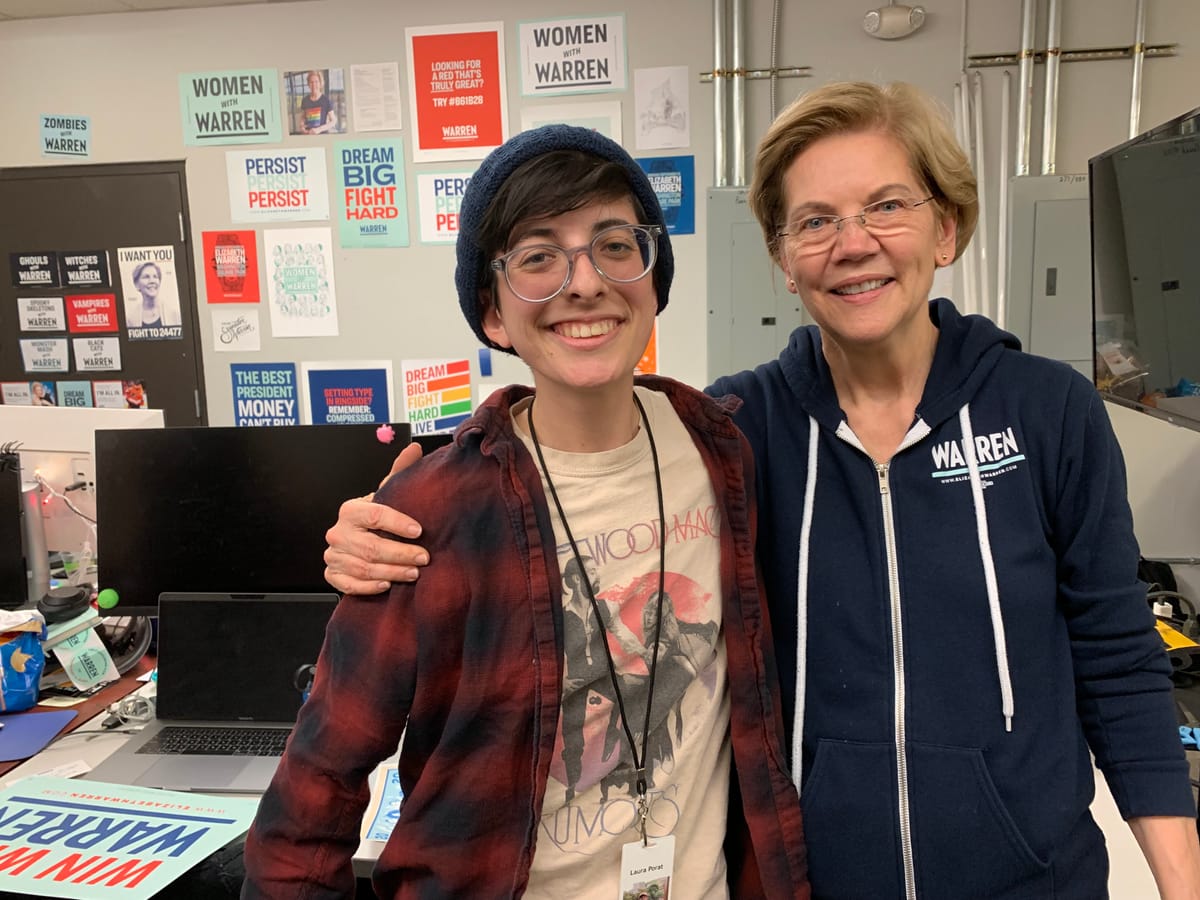

It was a cold, wintery day when I entered through the campaign headquarters in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The headquarters was set up in a large vast, warehouse made of makeshift tables with plastic chairs and lamps stacked on top of cardboard boxes. Campaign “fan” posters adorned the walls. Dogs with Warren, Cats with Warren, LGBTQIA with Warren, and so on. I had expected something more like The West Wing—people in sharp suits sitting at wooden desks and writing with a fountain pen. Instead, the headquarters was reminiscent of a college dorm—low budget and scrappy.

Working on a campaign was wild. It was my first time navigating the maze of comms and legal. The list of things we couldn’t do was longer than the things we could. Everything was high-stakes and tightly regulated. They wanted no whiff of even the slightest scandal.

Also—surprise! We were expected to work seven days a week and always be reachable beyond business hours. Still, I was young and energetic. I had the attitude that I had to do whatever it took for us to win.

I was the only Motion Designer on staff, which meant I spent a lot of time explaining what motion graphics was. I constantly pitched ideas for animated content. Explainer videos, data visualizations, animated GIFs, instagram stories and so on. It was surprising being surrounded by people who had never worked with an animator before. I was used to working at animation studios in LA where everyone spoke my language. This was different.

During the campaign, they heavily encouraged us staffers to do canvassing so one weekend, the entire design team and I went up to New Hampshire to knock on doors and talk to potential voters. Surprisingly, I encountered a lot of Amy Klobuchar voters up there.

Elizabeth Warren held a rally there and I got to meet my boss for the first time.

A few days later, Super Tuesday happened and our entire campaign sank overnight. We held a “funeral” at the office where we drank our sorrows away.

Warren dropped out two days later. And just like that—we were all out of jobs. To make matters worse, a global pandemic hit, shutting the entire world down.

I moved back in with my parents in LA and wondered what my next steps were.

A few weeks later, a friend from the Warren campaign hit me up—she was now working for Joe Biden and asked if I knew any motion designers who were interested in joining the campaign. I hesitated. Then I said, “Yeah. Me.”

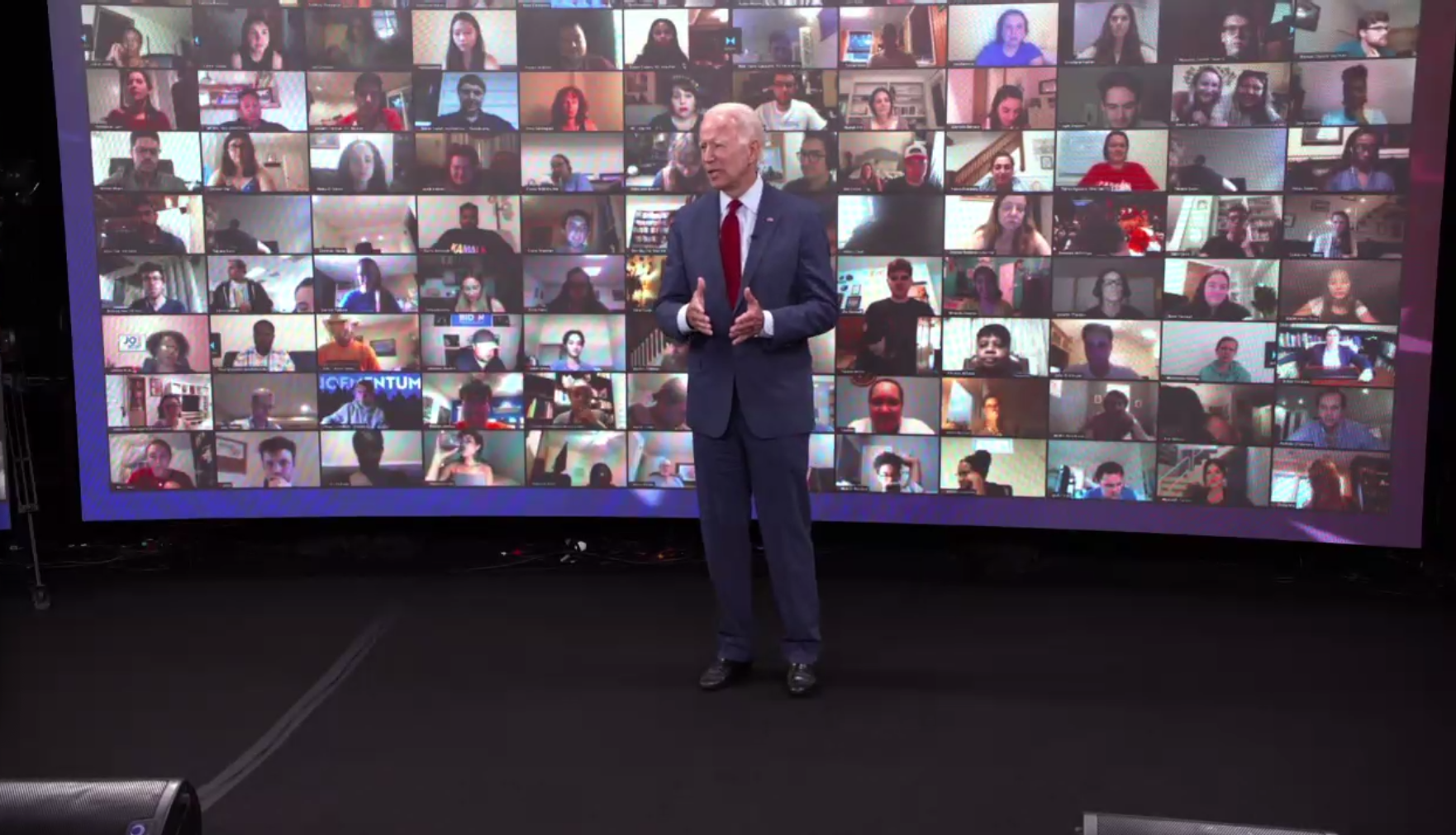

I joined the Biden campaign in July 2020—virtually, from my (Republican) parents’ house in LA.

The Biden campaign was a lot different from the Warren campaign. Since we were no longer in the primaries but running a full-fledged presidential campaign, we had more money to spend—and a much larger digital team. I was one of three motion designers, and it felt more like a well-run production studio than an indie startup.

Right away, I was busy animating. With COVID shutting everything down, animated content became more important than ever—our ability to film was limited. I animated data visualizations, designed our Instagram Story templates, created filters, made explainer videos, GIFs, and more. I was busier than ever.

November 3, 2020 came around. I was beyond nervous. We didn’t get results that night and the wait was painful. Not even waiting on college decisions felt this bad.

Finally, on November 7th, it was called.

We’d won!

The relief was unreal. It was the most incredible feeling ever. All of my blood, sweat and tears had finally paid off. At this point, I had been working for a year to ensure that Donald Trump wasn’t re-elected.

A few days later, I got a phone call from the digital director of the Biden-Harris campaign. He asked if I was interested in joining the post-campaign transition team—which meant my job wasn’t quite over. I’d be helping create videos for the interim period between Election Day and Biden’s official inauguration on January 20, 2021. I said yes.

It was a small group of us who had stayed behind. The digital team had probably been around 50-ish people people and now only 7 people remained. We primarily made videos about Biden’s cabinet picks—I remember I edited a video about Tony Blinken’s background. It was a slower pace from the campaign but exciting nonetheless.

On January 19th, I had a farewell Zoom call with my campaign friends, Becca and Joy. When 6 p.m. hit, I was suddenly booted from Zoom like I’d been Thanos-snapped. Locked out of everything. Just like that—it was over. I had served my duty to the campaign.

I returned back to my freelance life but I missed working on a campaign. It was such a fast-paced and dynamic experience that constantly required problem solving abilities and the ability to improvise when things went wrong. Nothing compared to it. I knew I wanted to work on a campaign again.

When Biden was gearing up for re-election, I was ready. I kept tabs on the job postings. One day, I saw a Video Lead role open up and knew that was mine. I interviewed for it and got the job, obviously. Onwards onto Wilmington, Delaware.

As Video Lead, I had to build a motion team from scratch. I knew plenty of talented animators, but convincing people to temporarily relocate to Delaware? Not easy.

Also—no one was excited about Biden.

I sent out so many emails to pretty much every animator I knew. Most people said no. The few who were interested weren’t the right fit. I needed animators that were fast, flexible, and good-humored. As one of my animators put it:

“You enter work at 9 a.m. and work on a video. By 11 a.m., it’s dead and you’ve moved onto something else.”

You have to always stay on your toes. Not just anyone is cut out for this. Finding animators that fit that description was a hard task but I eventually assembled my team.

The first month felt like treading water. Biden would flub something on TV and we’d just look at each other and sigh. We liked Biden, but man, he did not make our jobs easier.

The debate between Biden and Trump was the final nail in the coffin.

It was a Sunday and it was a nice, sunny afternoon in Philadelphia. I had done some light shopping and was in line at a coffee shop, waiting to order. I was in line at a coffee shop when I got a text from Robyn—my former CD from the 2020 campaign.

“Sorry Biden dropped out.”

I blinked.

“What???” I texted back.

She was incredulous. “No one told you?” She linked me to Joe Biden’s instagram post. I scrolled through it in disbelief. No way was this true. He couldn’t just drop out like that.

My turn to order.

“Hi, I’d like an iced latte please,” I said. My ability to stay stone-cold calm during distressing times is remarkable. Disassociation skills: 10/10.

I ran home to the apartment I shared with two campaign coworkers. We stared at a laptop, waiting for our bosses to tell us what was happening.

I cried. I was convinced Joe Biden had just lost us the race and this played into a Trump victory.

The Zoom meeting began and our bosses assured us all we had jobs still. We would operate the same as normal. The only difference is that we were now the Kamala Harris campaign.

The next day felt like a fever dream. People buzzing with nervous excitement. Joe Biden posters quickly replaced with Kamala Harris posters. The design team scrambled to rebrand everything.

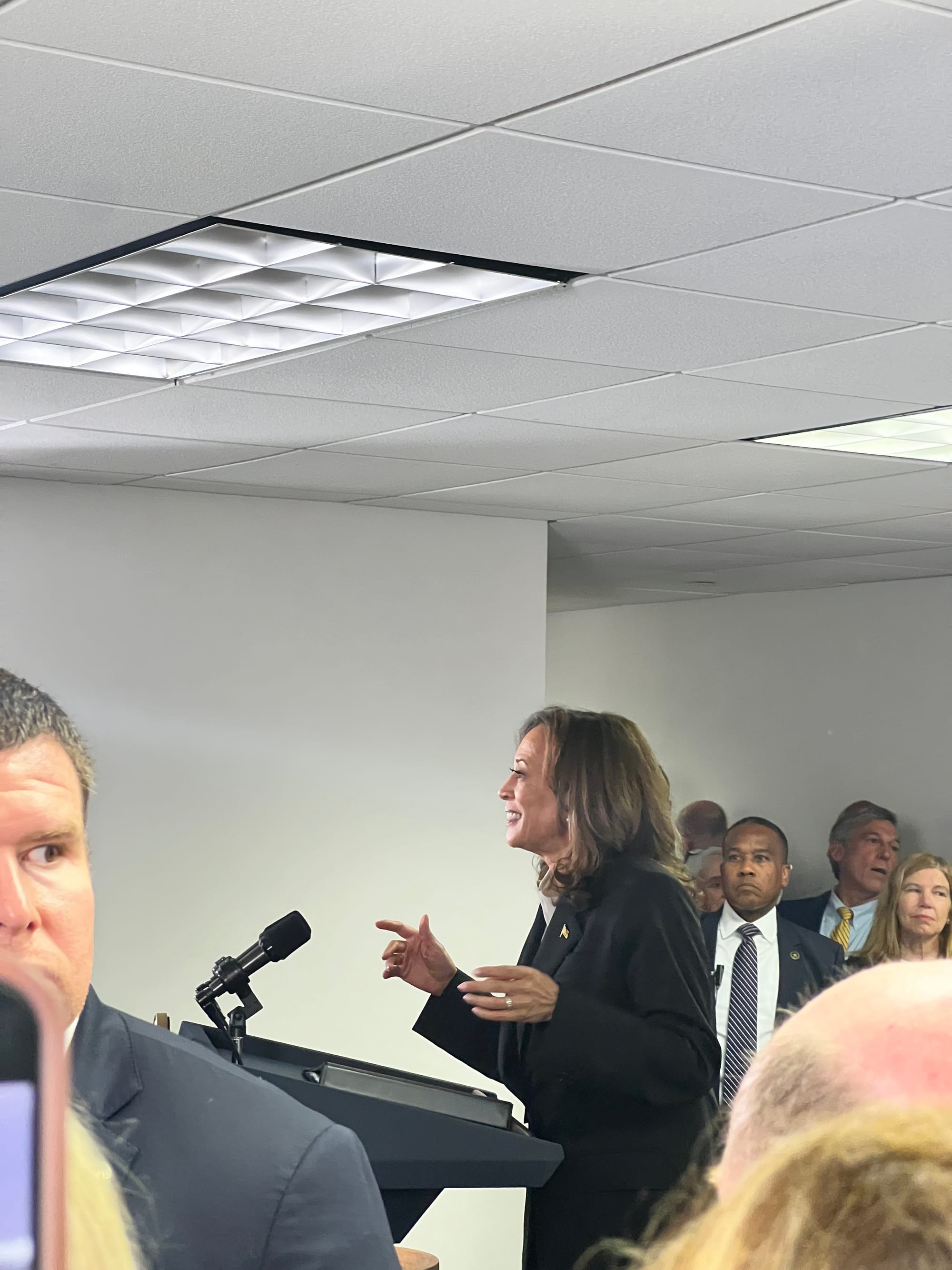

Then we got wind that Kamala Harris was going to swing by the headquarters so we all rushed to the section of the office she was going to be in and were greeted by Secret Service agents who searched us before we were allowed through. Doug Emhoff rushed through the crowd of staffers and gave people high fives. It was surreal.

Kamala gave her speech and the energy in the crowd was infectious. All of my friends texted me, suddenly asking if there were any job openings on the campaign. Posts on social media were overwhelmingly positive about the switchover. I began to have hope—maybe this would work out.

The problem? Most people didn’t know Kamala Harris. Not really.

We had 100 days to fix that.

We made videos about her background, her policies, her family. We had limited footage and the team worked nonstop.

Now that Kamala was the candidate, all the chatter was about who she would select as her Vice President. Funnily enough, this seemed to be even more important than whoever was at the top of the ticket. Her VP pick would signal the direction Kamala planned to take her presidency. Would she go with someone flashy and outspoken like Josh Shapiro? Or would she choose someone more moderate to balance out the fact that she was a Black and Asian woman with a progressive record?

The video team had no idea as to who she would choose, so we prepped videos for all the possible candidates—ready to drop the moment she made her announcement. As we all know, she eventually settled on Tim Walz, and the other videos we made will never see the light of day.

My motion graphics team worked on both social media content and paid ads. Part of our paid strategy involved persuasion videos aimed at specific audiences. To test their effectiveness, we’d show these videos to focus groups and gauge their responses. I sat in on one of those meetings—virtually—and the response was infuriating.

This particular focus group was made up of moderate white women, leaning either slightly Democratic or slightly Republican. The moderator asked them about their thoughts on Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. Many of the women said they didn’t really know who Kamala Harris was or what she’d done as Vice President. One woman complained that Kamala laughed too much—said her laugh sounded more like a “cackle.” Another said she thought Trump would be a better president because he was more respected on the world stage. The barely concealed sexism was disappointing, but not surprising. These women weren’t alone or unique in their thoughts. They reflected a large swath of American values.

We kept pushing out videos about Kamala’s background and her proposed policies. But we were racing against time. We had 100 days to introduce her to the country, while Trump had been campaigning for close to a decade. His name recognition was insurmountable—it wasn’t close.

I blinked, and Election Day was here. I was nervous but cautiously hopeful. The online energy around Kamala had been good, but those focus groups lingered in my mind. I didn’t know if it would be enough. If a white woman couldn’t beat Trump, could Kamala? She had both racism and sexism stacked against her.

We gathered in the office around the TV, waiting for results. The mood was muted and anxious. By 11 p.m., more red states than blue were being called, and I think we all started to see the writing on the wall, even if we were still clinging to hope. It was just the red mirage, right?

Around 1 a.m., our Creative Director walked in and told us to go home—we wouldn’t hear anything until the next day. The election hadn’t been called yet, but we were told to prepare for anything.

We glumly walked back home and I fell asleep around 3 a.m., hoping that I would wake up and Kamala Harris would be announced as the winner.

I woke up the next day, and Donald Trump’s image smirked at me from my phone screen.

So what’s my takeaway from working on three political campaigns and losing two of them?

First: Electing a female president is hard. Yes, many other countries have had female leaders, but it’s not a fair 1:1 comparison. For example, Prime Ministers are chosen by smaller governing bodies—not by 150 million individual voters. In places like the UK, people vote for the party, and the party picks the leader.

Second, the U.S. is big. Like, really big. Think of how difficult it is to work in a group project. Everyone has their own opinion and there’s a bunch of slackers you have to drag through in order to make sure the project is finished. Apply that same mentality to electing someone to be president. Everyone in America has different thoughts and opinions about who the president should be and what values they prioritize. No single candidate can please everyone.

Expanding on that point: grouping entire demographics together is lazy and misleading. You’ll hear Democrats talk about the "Latino voting bloc," but anyone who’s spent time in Spanish-speaking communities knows Cuban-Americans and Mexican-Americans are worlds apart politically and culturally. Just because they speak Spanish doesn’t mean they vote the same. There’s always nuance.

Third, motion graphics in politics is still a relatively new concept—and it's both underutilized and under-appreciated. I’ve spent the past five years advocating for and educating people about the power of motion design. It’s not just cartoons. It’s a tool to inform and persuade. And I’m not just talking out of my ass—I’ve got the numbers to prove it. During the Biden-Harris transition, I created an entirely animated video introducing Biden’s cabinet picks. It racked up over 5 million views and became the most-watched video of that entire period. On the Harris-Walz campaign, my team produced animated content that was tested with focus groups—and it effectively shifted opinions. Motion Graphics is a powerful tool.

Toward the end of the Harris-Walz campaign, my boss confided in me that having four Motion Designers hadn’t been enough. He was right. I firmly believe a successful campaign needs an army of Motion Designers—people who are fast, design-savvy, skilled animators, and solid editors. They’re way more cost-effective than hiring separate video editors and graphic designers. Not to say those roles aren’t important—they are—but Motion Designers bridge both worlds. If a campaign’s on a budget, their best bang for the buck is a solid crew of Motion Designers.